Teresa De Anda was a pesticides activist in California’s San Joaquin Valley who died of liver cancer in 2014. Read on to learn about her life in her own words. See also the resources available in the menu at the upper left of the screen by hovering over the star symbols.

Earlimart, CA. May 1999.

Once there was a guy spraying [pesticides], it was May, 1999, and he was spraying over there and the fog was in the house. He wasn’t even turning off the tractor rig when he was coming up the road. The stuff he was spraying, it was in the house. My kids were all puking, my husband was out of town, so it was just me here. I didn’t know to pick them up, take them to the van, and get them out of there. It looked like London fog out there, and in here it looked like San Francisco fog. I didn’t know whether to leave them sleeping, or to take them out to more danger. So I called the fire department, the sheriff, and they both said the same thing: “The farmer has a right to farm. You can’t complain about this.” And I said, “But I don’t know if we’re going to die or live or what. This stuff, it’s really bad out here. I know he’s got to spray, I realize that, just tell him to turn the things off when he’s coming out of the vineyards.” You know what a tractor rig looks like? Kind of like a monster. It’s a noise, and then you look out, and then there’s lights. It was in the night, so they said that they couldn’t come out. I said, “You’d better come out here and at least look at this.” I wanted it on record that I called them.

And so I had always through the years been complaining and getting into it with the farmer. And before that too, when Anthony was about three or four, we were out on the lawn, and then the guy was spraying, and it drizzled on us. It actually got on us, and so I called. I don’t know, I guess I called poison control, ‘cause I never knew who to call. A guy came out, and he took our clothes, and then a couple of days later, he said “How’s Anthony doing?” And I said, “Well, he’s been kind of just laying around and not really moving a lot. But he does that, ‘cause he’s autistic. So I don’t know if it’s the autism, or I don’t know if it’s the spray.” And I said, “Why, is it dangerous?” And he said, “Yeah, well there was traces on your clothes, and so just watch him closely, and if you notice anything different about him, then let us know.” And I’m like, “Okay.” They didn’t give me information, they didn’t tell me, “Next time it happens, you have a right to call and fight the farmer, this is a pesticide,” nothing. So I was still in ignorance. I was ignorant, ignorant, ignorant. Meanwhile, I was fighting for Anthony’s rights, because he’s autistic, so with the IEPs and stuff, and getting an advocate. IEP is an Individual Educational Program that kids with special needs are entitled to. Most parents will go in there and trust the teachers to do what they think is best, and I don’t. I’ve had the biggest IEPs, because I’ve really been concerned that what they’re doing is not the right thing for Anthony, so I want it my way. Elementary was hell. The first four years of his education, it was really hard, always fighting with the principal, fighting, fighting, fighting. They wanted to take his teacher’s aide, I said “No, he needs the teacher’s aide.” Finally when he got to Alila School, which is fourth and fifth grade, I would say something and, “Okay, Mrs. Anda,” they wouldn’t argue at all. “And I think he needs…” – “Okay, Mrs. Anda.” I wouldn’t even finish the sentence, “Okay Mrs. Anda.” So that’s how it was after that. But I really fought a lot for him too. So advocacy stuff, I was doing that early.

And so I had always through the years been complaining and getting into it with the farmer. And before that too, when Anthony was about three or four, we were out on the lawn, and then the guy was spraying, and it drizzled on us. It actually got on us, and so I called. I don’t know, I guess I called poison control, ‘cause I never knew who to call. A guy came out, and he took our clothes, and then a couple of days later, he said “How’s Anthony doing?” And I said, “Well, he’s been kind of just laying around and not really moving a lot. But he does that, ‘cause he’s autistic. So I don’t know if it’s the autism, or I don’t know if it’s the spray.” And I said, “Why, is it dangerous?” And he said, “Yeah, well there was traces on your clothes, and so just watch him closely, and if you notice anything different about him, then let us know.” And I’m like, “Okay.” They didn’t give me information, they didn’t tell me, “Next time it happens, you have a right to call and fight the farmer, this is a pesticide,” nothing. So I was still in ignorance. I was ignorant, ignorant, ignorant. Meanwhile, I was fighting for Anthony’s rights, because he’s autistic, so with the IEPs and stuff, and getting an advocate. IEP is an Individual Educational Program that kids with special needs are entitled to. Most parents will go in there and trust the teachers to do what they think is best, and I don’t. I’ve had the biggest IEPs, because I’ve really been concerned that what they’re doing is not the right thing for Anthony, so I want it my way. Elementary was hell. The first four years of his education, it was really hard, always fighting with the principal, fighting, fighting, fighting. They wanted to take his teacher’s aide, I said “No, he needs the teacher’s aide.” Finally when he got to Alila School, which is fourth and fifth grade, I would say something and, “Okay, Mrs. Anda,” they wouldn’t argue at all. “And I think he needs…” – “Okay, Mrs. Anda.” I wouldn’t even finish the sentence, “Okay Mrs. Anda.” So that’s how it was after that. But I really fought a lot for him too. So advocacy stuff, I was doing that early.

Earlimart, CA. November 1999-2000

Our street was the first street to get evacuated [after the pesticide drifted off the fields and into our neighborhood]. I’d driven to Delano, and when I came back there was a sheriff standing at our gate. It had just gotten dark, and my husband said, “We need to get out, because there’s something happening.” I smelled it a little bit, but I didn’t smell it that strong. But I was still very disturbed. It’s a horrible feeling, getting told you’ve got to get out, that there’s something that you shouldn’t be smelling. I got the kids, and we left in the van. My husband got my blind uncle and my 87-year-old compadre, and then we drove. But I was just so fearful for the people that were staying.

Our street was the first street to get evacuated [after the pesticide drifted off the fields and into our neighborhood]. I’d driven to Delano, and when I came back there was a sheriff standing at our gate. It had just gotten dark, and my husband said, “We need to get out, because there’s something happening.” I smelled it a little bit, but I didn’t smell it that strong. But I was still very disturbed. It’s a horrible feeling, getting told you’ve got to get out, that there’s something that you shouldn’t be smelling. I got the kids, and we left in the van. My husband got my blind uncle and my 87-year-old compadre, and then we drove. But I was just so fearful for the people that were staying.

Days later, we found out what happened to everybody. I had read the newspaper, but it didn’t mention what happened to the people that Saturday night, November 13, 1999. On Wednesday the UFW [United Farm Workers] had a meeting and they had all the agencies there: the county ag commissioner, the fire department, an expert on pesticides, Pesticide Watch. It was just packed with mad, angry people. That night, I found out what had happened when we left.

[After the pesticide drifted over the town] the people who were the sickest, they were told to go to the middle school. And at the middle school they told the men, women, and children to take off their clothes and go down the decontamination line. Keep in mind: these people were vomiting and had burning eyes, just coughing and coughing, and so they were scared to death. They were given no privacy, just two tarps on either side, and they were told to take off their clothes. And the people didn’t want to.

One lady said, “Where’s my rights? Where’s my rights?” They told her, “Listen, you have no rights tonight; you’ve lost your rights.” And so she took off her clothes, and she said that that was the worst feeling in the world, because her kids had never seen her without her clothes, and they could see her. This is indicative of how they did the decon [decontamination]. She took off everything, absolutely everything, but she wouldn’t take off her underwear, so they yanked it off. They yanked off her Nikes, and so there she goes through the decontamination line, which was a fire-department water hose,* on a cold November night. A fire-department water hose with a guy standing there holding it. She went through one line and then the other, but they didn’t wet her hair. At the end of the decon line, they were supposed to have ambulances waiting. But the ambulances weren’t there yet, so they just gave them little covers and told them to sit on the ground.

So I’m finding all this stuff out at the meeting. All these mad people are just yelling at the agencies, telling them, “How could you do this to us?” And then they told us what had happened at the hospital. The people did get transported to the hospital. Some went to Tulare Hospital, some went to Porterville Hospital, some went to Delano Hospital. Well, the lady with a lot of kids, she was babysitting kids too. They couldn’t take all of her kids to the same place, so they wrote their phone numbers on their stomachs, like they were animals. At the hospitals, they took their information, their names, their number, their address, but they didn’t even triage them. The doctor called poison control, and poison control said, “There’s nothing happening to them, just tell them to go back home but to try not to get re-exposed.” That’s all poison control told them. So they were sent on their way and they were given the clothes that they had been in before they got decontaminated. They just gave them back to them. Didn’t have them cleaned.

So I started learning more and getting more and more angry. I couldn’t sleep at night, ’cause I was so upset at how it had changed my kids’ health and my health. When I was growing up, my dad had always said, “Trust the government. The government’s never going to lie; the government’s good,” and all that.  And I thought, “No, they’re not,” because they really let us down that night, they really, really let us down. So much for trusting the government. I couldn’t sleep at night because it bothered me so much that it happened and that still nothing was being done about the people who had gotten sick. I learned a lot about pesticides. And then at press conferences they would always ask me to speak. Even though I wasn’t one of the victims that got deconned, I was one of the ones speaking all the time. They were calling me for meetings and conferences and stuff to talk about what had happened.

And I thought, “No, they’re not,” because they really let us down that night, they really, really let us down. So much for trusting the government. I couldn’t sleep at night because it bothered me so much that it happened and that still nothing was being done about the people who had gotten sick. I learned a lot about pesticides. And then at press conferences they would always ask me to speak. Even though I wasn’t one of the victims that got deconned, I was one of the ones speaking all the time. They were calling me for meetings and conferences and stuff to talk about what had happened.

[Soon after that] Linda MacKay invited me to go to a Center on Race Poverty and the Environment’s advisory board meeting. So then I thought, “Wow, there’s more people like me that read the newspaper and that care about things.” I couldn’t believe it, that there’s other people that actually read a newspaper, watch the news and like the news. I mean, now I know that the news is a lot of lies, but you know, you’ve got to filter what you believe and don’t believe.

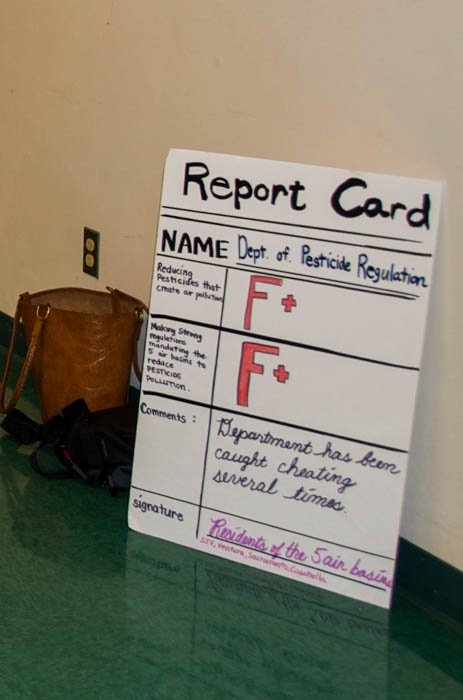

What happened in Earlimart was in November. The UFW and us, we formed El Comité Para el Bienestar de Earlimart [Committee for the Well-Being of Earlimart]. All of the people were victims of the accident. They were all mostly farm workers. Just a couple weren’t. We started having meetings, our own meetings without the UFW, still supporting the UFW in any press conference they wanted us to, but then we started having our own meetings, and then they became monthly meetings. The ladies that were in El Comité, like Eramina and Josephina and Guadalupe, they were just very outspoken. And where one lady, Bartola, wouldn’t speak at all, now she was speaking. At the meetings, she was just real quiet all the time, and now she was speaking her voice. So in May of 2000, we had a big meeting, and we called DPR, the Department of Pesticide Regulation. So the head of DPR came, the county ag commissioner came, different political people came. I mean, I remember when we were faxing out the forms, inviting them. We invited the President, we invited everybody. We just invited, invited and invited. Faxed Barbara Boxer, Feinstein, everybody. Cal Dooley. And some of their representatives did show up at that meeting. It was supposed to be an informational meeting, but where we sat them, they were in the front. So we were just, like, asking them questions about pesticides and stuff. And together with the UFW, we had asked the county commissioner that we needed a hotline for when these accidents happen. So when he walked in, and it was Leonard Craft at that time, he said “Here you go Teresa, here’s your number that you can call anytime, and they’ll come out and see about drift.” I said, “Oh my gosh!” So we had already won one victory. And that was just really quickly. Just by asking, we got that.

Meanwhile, in Earlimart, because of all the attention to pesticides, the farmer across the street right here – those were all vineyards there. He took those out. Those have been out since 1999. He made his own buffer zone there.** And he owns more on Avenue 56 over there, and he took those out too. He pushed them back, about 100 feet. But it’s made so much difference, just being back. Because those are table grapes. Table grapes use all the really nasty stuff. Raisins and stuff, they use sulfur, but not the captan and all that.

And then in September of 2000, we had asked for the farmer or the chemical owner to pay for the medical payments for the people that had asthma, because it was all coming out that people had gotten asthma, didn’t have it before that night in 1999, when they went to the doctor, they had gotten asthma, just like that, from that night, that exposure. And it had gotten in their mucus membrane, and then in their lungs. And either it’s RSV, Respiratory something something, or it was asthma. And so they needed long-term treatment. We got Wilbur-Ellis to pay for that. We had a big press conference, right here at the house. And that was a big victory. The State of California Department of Pesticide Regulation gave Wilbur-Ellis the biggest fine that had ever happened. It’s still peanuts compared to other fines for toxic spills and stuff, but it was the biggest for pesticides. It was $150,000, and $75,000 went for the treatment of the victims. We had gone around, and we had gone door to door to see who was exposed and who wasn’t exposed, and we found 100 people that were exposed. The government would’ve kept it at the number of 24, but we wanted to get the full extent of it. And when we did that first door to door, we only stayed on this side of Avenue 48, we didn’t go beyond over there. But later on, I did go beyond Avenue 48, and I got a total of 500 people that had been affected.

And then in September of 2000, we had asked for the farmer or the chemical owner to pay for the medical payments for the people that had asthma, because it was all coming out that people had gotten asthma, didn’t have it before that night in 1999, when they went to the doctor, they had gotten asthma, just like that, from that night, that exposure. And it had gotten in their mucus membrane, and then in their lungs. And either it’s RSV, Respiratory something something, or it was asthma. And so they needed long-term treatment. We got Wilbur-Ellis to pay for that. We had a big press conference, right here at the house. And that was a big victory. The State of California Department of Pesticide Regulation gave Wilbur-Ellis the biggest fine that had ever happened. It’s still peanuts compared to other fines for toxic spills and stuff, but it was the biggest for pesticides. It was $150,000, and $75,000 went for the treatment of the victims. We had gone around, and we had gone door to door to see who was exposed and who wasn’t exposed, and we found 100 people that were exposed. The government would’ve kept it at the number of 24, but we wanted to get the full extent of it. And when we did that first door to door, we only stayed on this side of Avenue 48, we didn’t go beyond over there. But later on, I did go beyond Avenue 48, and I got a total of 500 people that had been affected.

Some people that went to the hospital weren’t even told that there was an accident that night. People that had two of their kids vomiting all the way to Delano, and the mom says to me, “Oh my God. That was the night where there were all those ambulances, and the pesticides is what did it?” And I said, “Yeah, that’s what did it. The hospital didn’t tell you it was related?” “No.” “You told them you were from here?” “Yeah.” But that’s all changed now, because of all the stuff we’ve been doing. I think with all the attention, and any time any town is aware of people knowing about what to do with pesticide drift, then the farmers are more careful, because they know that the people aren’t just going to sit there and accept it. Look at all the years I took it, and just accepted it. It would happen so often that Anthony, my son with autism, would come in when the tractor would be spraying, and he’d say “Mommy, mommy, mommy!” “What Anthony?” “The tractor, the baddie tractor!” Because he would put a suffix at the end of words, so, “the baddie tractor, the baddie tractor!” So, “They’re spraying, it’s going to give me the headache again. What do I do, what do I do? Call the police mom, call the police!” He’d be telling me that. So it would just happen, over and over and over. We just accepted it.

El Comité Para el Bienestar de Earlimart started going to other communities and telling them that pesticide drift shouldn’t be happening. And every town we went to, they would say that it was happening there. And they would say, “You mean we can call and complain about that?” Yes, you have to complain.

By that time we had formed a relationship with the county agricultural commissioner. When the spraying season was going to begin, say in April, we’d call the county agricultural commissioner down here, and I’d say, “Okay, what is drift? Explain it to us so we’ll know what to tell people to look for, and we’ll know when they can call and report it, and when it’s not drift.” Because here it smells all the time of pesticides. But for it to technically be drift, then they need it to be drizzling and leave some kind of evidence that it’s been there, even though we have scientists that argue that drift is just when you can smell it, because the molecules are in the air, and it’s going in your body, your bloodstream and your brain. But the county needs evidence to prove it. Because if the farmer does fight it, the county commissioner needs that evidence to give the farmer the fine. If you don’t have the evidence, he’ll just fight it and win.

the county agricultural commissioner. When the spraying season was going to begin, say in April, we’d call the county agricultural commissioner down here, and I’d say, “Okay, what is drift? Explain it to us so we’ll know what to tell people to look for, and we’ll know when they can call and report it, and when it’s not drift.” Because here it smells all the time of pesticides. But for it to technically be drift, then they need it to be drizzling and leave some kind of evidence that it’s been there, even though we have scientists that argue that drift is just when you can smell it, because the molecules are in the air, and it’s going in your body, your bloodstream and your brain. But the county needs evidence to prove it. Because if the farmer does fight it, the county commissioner needs that evidence to give the farmer the fine. If you don’t have the evidence, he’ll just fight it and win.

Arvin, CA. 2002

In July of 2002, there was another drift incident. In Arvin. It was the same pesticide as in Earlimart. We wanted to go talk to the people. I wanted to let them know that when the doctors and the agencies, like the fire department or whatever, tells you it’s nothing – because they will, they’ll tell you it’s nothing. They’ll say “Oh, it’s mass hysteria, you’re hung over.” Or, “It’s just something you ate that’s making you nauseous.” No, it’s the pesticides, and don’t doubt it. It’s the pesticides. Then I always want to tell them that they need to report drift. It’s state law, drift is illegal, it shouldn’t happen. The farmers spray the field, it leaves the field, goes on your car, goes on your property, goes on the park when you’re there. You need to report it. I’m trying to get it across, but people still don’t call. The numbers are so low for reports.

The TV said that it was only one lady that went to the hospital. And I said there’s no way just one person could get sick when it’s that pesticide. If it’s Arvin, my God, it’s got to be something like Delano, or at least Pixley. For one person to get sick out of all those people? No. So we end up going out, Joe Morales and Linda MacKay and myself, and we went door to door. We went door to door, and that night we got 42 people that were affected, just in maybe five houses, because a lot of people live in one house, like mine. So the metam sodium was on the field, just east of Judith and Barbara Streets. Now we had only gone on Judith Street to a couple of houses, and we found so many sick people. The stories sounded identical to Earlimart. The burning eyes, the vomiting, the coughing, the inability to breathe. It was like Earlimart all over again. But the difference in Arvin was that they weren’t even evacuated.

One lady that we talked to that night, her story makes you cry. She said that all of a sudden that day, that her kids were vomiting outside. She went outside, and boy it smelled real bad. She saw the fire department down the street, with an elderly white lady that got taken to the hospital. And she said there was one ambulance there. She goes, “I guess if it was dangerous, they would tell us to get out.” She said, “But we got so sick that we had to call for help.” So somebody from the fire department did go out there, and they sniffed around. They sniffed the gas heater, the water heater, the stove, and they didn’t find anything. They walked by her husband that was vomiting in the bathroom. You could hear him just vomiting. They walked by the kids and they are just vomiting, and they said they didn’t smell anything, and they left. They left them there. And it was a hot July, so they had the swamp cooler on. She said, “I thought we were going to die. I thought it was an atomic bomb. I thought it was Osama bin Laden. I thought he had thrown a bomb and that it had hit around here. I thought we were going to die. I didn’t know whether to turn on the cooler, turn it off.” It’s just crazy. It was stories like that, identical to ours. Her husband couldn’t even drive because he couldn’t see, because his eyes were burning. They went next door, and their neighbors had an air conditioner. So they went in there, and they felt a little relief. But other than that, they were totally messed up, their health. It was just really bad.

We hadn’t gone out there until a month later. It happened on July 9. We didn’t go out until August 9, because all this time I had been calling the ag commissioner in Kern County, and telling him, “Are you going to go out there and check those people?” And he said, “What people?” And I said, “The ones in Edmundson Acres, the ones in Arvin.” He said, “Well, I don’t think so, because I don’t think we should. We got one person in the hospital, and that’s all that got sick.” And I said, “No, you need to go out there and talk to the people, so that you can find out how many got sick.” And he said, “Well, I’ll see if Environmental Health can do it.” So he put it off another couple of weeks. I waited a couple of weeks, and called him again. I said, “Did Environmental Health go out there?” And he goes, “Well Teresa, honestly I think what’s important is how the accident happened. I think how many people got sick doesn’t really matter. But look, I’ll try to get Environmental Health to go out there.” So he put it off a couple more weeks. So that’s why that whole month lapsed. The last time I called him, I said, “Are you going to go out there and check those people, to just talk to them and see how far it drifted, so you can do it for your report?” I was trying to work it so he would see it was beneficial to him to go out there. And finally he said, “You know what, I’m just not going to go out there. What’s important to me is how the accident happened, not how many people got sick.” We went out there the next day.

We hadn’t gone out there until a month later. It happened on July 9. We didn’t go out until August 9, because all this time I had been calling the ag commissioner in Kern County, and telling him, “Are you going to go out there and check those people?” And he said, “What people?” And I said, “The ones in Edmundson Acres, the ones in Arvin.” He said, “Well, I don’t think so, because I don’t think we should. We got one person in the hospital, and that’s all that got sick.” And I said, “No, you need to go out there and talk to the people, so that you can find out how many got sick.” And he said, “Well, I’ll see if Environmental Health can do it.” So he put it off another couple of weeks. I waited a couple of weeks, and called him again. I said, “Did Environmental Health go out there?” And he goes, “Well Teresa, honestly I think what’s important is how the accident happened. I think how many people got sick doesn’t really matter. But look, I’ll try to get Environmental Health to go out there.” So he put it off a couple more weeks. So that’s why that whole month lapsed. The last time I called him, I said, “Are you going to go out there and check those people, to just talk to them and see how far it drifted, so you can do it for your report?” I was trying to work it so he would see it was beneficial to him to go out there. And finally he said, “You know what, I’m just not going to go out there. What’s important to me is how the accident happened, not how many people got sick.” We went out there the next day.

So we had gone up there that day. Then we went out there on a second trip, and a reporter just so happened to be interviewing me that day. She went up there with us, and she had a camera guy with her, and the first person I was talking to right there was Soyla Gasca, and she had her baby in her arms. Soyla said, “Well, my baby just got so sick. It’s been a month, and now I’ve had to take it to the doctor so many times. He can’t stop coughing. Asthma.” And she was a young mom, she was like 16, she looked like a little baby herself. She’s holding this baby, and she goes, “I just threw him in the water, I didn’t know what else to do. And he was just crying and screaming cause his eyes were burning so bad.” And so they took our picture, and they quoted me as saying, “The county should be out here doing this, what we’re doing, but since they’re not, then here we are.” And then that hit the fan. Then it went to the Department of Pesticide Regulation. All the complaint forms that we were getting, I was faxing them to Department of Pesticide Regulation and to the county commissioner, and to San Francisco, and to Sacramento too, so that everybody could see all of these symptoms and how severe they were. So many stories. So that was Arvin. In the end the Department of Pesticide Regulation took over the investigation, and they ended up finding 252 people that got sick that day, instead of the one that would’ve gone on record.

Weedpatch and Lamont, CA. 2003

Now Lamont happened in 2003, on October 3 and 4. But before that, there was a newspaper article that came out about a guy named Ignacio Azpitarte, and they had him with a camcorder, and it says this man is filming everything, and he’s reporting pesticide drift. So I wanted to go meet him. I drove out to Weed Patch, and honestly, I didn’t even know how to get to Weed Patch. I just got on Weed Patch Road, and I drove out there. And if you know how these roads are, I mean it would be like you trying to go to Richgrove. You wouldn’t know how to go. That’s how I was. I was going blindly out there. I actually went too far, and then I had to go back, and I was asking people. So I felt like a detective going out there and doing this. And then I called the directory for the Azpitarte in that town, and they said “No, but he’s my brother in law, and he lives right here by me.” And so I went down there, and I met him.

They lived in a really small little shack, kind of, that had wheels all around. It was a rural house, it wasn’t even two streets, and that street didn’t even have a name. It was just like a dirt road in there, and there was his house. I went there, and he was there. So I met him, and I said, “I just want to know what you’re doing and stuff.” And he said, “Oh, I’m taking video of all this.” He says, “One time I was walking in the morning, and a helicopter was spraying, and it got on me. And I got so dizzy that I was holding on to the post. And I had my cell phone, so I called 911, and they took me to the hospital. And when they took me to the hospital, they said I had been drifted on.” But it didn’t start a pesticide investigation. And so I called the county commissioner and I said, “Why didn’t they do the investigation there? This is in the paper. I mean, obviously you guys heard about it, and the hospital, by law, they’re supposed to call the county commissioner when there’s pesticides.” And they said, “Well, the reason it didn’t go to us was because we’re worried about his heart, because he has an existing heart condition. So we treated the heart condition, we didn’t focus on the pesticides.” And I’m like, “You’re still supposed to do the pesticide investigation, because he had it all over his clothes and stuff, and that was evidence.” But what they did later on was they took him to the county commissioner’s office, maybe three months after I had talked to them, and they just grilled him. He was all excited when he went in, and he went in there naïvely. I used to be naïve and believing anything they tell me. And they said “Well, we want to see your video.” So they had him take his videos, and they just basically tore them to shreds, which is really bad, because we need them. But I told him, “Why didn’t you call me? Somebody could’ve gone with you, because you don’t go to those things alone, you never go alone. You’re supposed to take somebody with you.”

So the videos that he had were really good, they showed the crop spraying. And he even had signs that he had gotten off the fields. He said that his daughter, the year before, that she didn’t have asthma, she was little, like two months. And then after they were spraying this really bad stuff — and he had the sign of what they’re spraying, and it’s really nasty – she got asthma. So now she has a nebulizer, she has a little inhaler. So she was really affected by this. But that’s way too long ago to report her, to make a drift report on. But just the fact that he knew, he put those things together. And so he had his camcorder.

So on October 3 and 4, he had his camcorder. And he and I had been in touch, and we had been having meetings right there in Lamont, and trying to get other people interested. October 3 was a Friday. His place is west of Weed Patch Highway, and then on the other side of Weed Patch Highway, there’s fields there. And those fields drifted on to them that day — that night. Everybody had burning eyes, and they were calling for 911. 24 people were lined up on the street when the fire department got there, and those 24 people were saying they were coughing and their eyes were burning, and he got everybody. “So how do you feel right now?” Cough, cough, cough, and, “My eyes are burning!” He just got it all on video. Then he got the fire department guy on video. The fire department went in, and then he sniffed the stove and he gets into doing all that, and sniffs the water heater. And then the fire department guy goes, “Well, what do they grow around here?” And Ignacio is trying to tell him in his broken English, “It’s the field, it’s the field, that’s what’s here. It’s the field.” And the fire department guy goes, “Well, let me get on the phone with my supervisor.” And he called the supervisor, and the supervisor says, “Just tell them it’s something that spilled on the road. If you can’t smell it right now then it’s gone. Just tell them that it probably melted or that it evaporated, that it’s gone now. Tell them to go back into their houses, and if they’re still sick, they can call us back and we’ll go back out there.” On the tape, Ignacio had been telling them, “Don’t worry, don’t worry, help is coming. Don’t worry, they’re coming to help us now.” They just were so let down. A lot of people that could get out, got out that night. But a lot of them had to stay in that night. Got really sick.

The next day was a Saturday, and they applied the pesticide again. This time instead of going west, it went south. And south, there was a low-income housing complex, I guess about 100 people live there. They began smelling it, and they began getting sick, a bunch of kids out on the lawn vomiting. A bunch of people from that place were calling 911, calling for help. And basically, this is what happened from Flores’ point of view, Flores Baptista. She said she was babysitting her nine month old nephew. She was holding him in her arms. She has a lot of kids, all of her kids were outside, vomiting. And the baby was in her arms, and she was on the phone with 911, and she told them, “My kids are outside vomiting, there’s something going on here, we think it’s the spray. You need to come do something about it. Everybody’s kids are outside vomiting, and we just need some help out here.” And the operator told her, “Just hold on, we’re trying to figure out what’s going on. Just calm down. I think your being calm will have a big impact on your kids, and you need to just calm down.” And so Flores said, “OK, well I’m trying to relax, but my kids are out here, and they’re getting sicker and sicker. And the baby I’m baby-sitting is breathing really weird, and I’m really worried about him. I don’t know if he’s going to make it or not. And my nephew’s looking real bad!” And the operator kept telling her, “Look, you’re hysterical. You need to calm down.” This went on for 45 minutes. They kept them on the phone for 45 minutes! And so after 45 minutes, Flores said, “You know what?” and she said some bad words, and she said, “I’m just going to get out of here. I’m not going to wait for you guys. You guys obviously aren’t coming, and I don’t know what you’re doing, but everybody’s about to die here. We need to get out of here. It smells so bad.”

So she got in her van, and she drove out. And at that time, other people slammed the phone down. When they saw people leaving, they slammed their phone down, and they got out, and they were leaving too. And so there was a caravan of vans. They drove out to Sunset and Weed Patch. And on the corner, it was barricaded. It’s called a stop and freeze, or freeze and keep whatever is contaminated in. They were telling people “Go back, go back, you can’t come out.” And they’re like “No, we’re sick, and need our kids to get to the doctor. We’re going to drive them ourselves, ‘cause we’re not going to wait for you any more. We were on the phone for close to an hour with that lady, and she was just telling us to sit down, to calm down, and that we were talking crazy and stuff, but no, we’re going to get out.” And there was a lot of people that spoke Spanish. So one of the men just went on the dirt and drove off. Broke the barricade.

But when they saw that the people had broken the barricade, they said, “Okay, well go to the store, and we’ll have triage there, we’ll have medical facilities there.” And the medical facilities were tarps, different colored tarps, and according to the symptoms that the people were seeing, they would sit them on those tarps. And they had them there for close to five hours with no water, food, bathroom. Well maybe they had water. No, I don’t think they had water, ‘cause they didn’t want to onset the poison, whatever it was. So they didn’t even have water or milk or diapers for the babies. It was just crazy. And what kept those people in, the contaminated people, they had red tape surround them. So people that were trying to come and help them, you know, their family members, that they were calling on their cell phone. They wouldn’t even let them get near there. Then people who were driving up from the housing complex in their own cars, they weren’t let in. It was so unorganized, and so stupid, how it was done. And then right there they were, it’s called Weed Patch Store. So it’s on the same street. It’s too close. They should’ve been moved further. There’s so many things that went wrong that it’s just not right, because in the first place, if they would’ve caught it Friday, Saturday wouldn’t have happened. And so this one really pissed me off. It was just so bad, bad, and then it was number three. It’s like strike three, boom boom boom.

Meanwhile, I had been going to Fresno and meeting a lot of people that were working on air quality. I liked Fresno because there was a cluster of air quality activists. I always liked to work on air stuff, because I know that agriculture had a free ticket. They were exempt from the Clean Air Act. And I thought that was so wrong. So when I learned that Brent Newell was working with Senator Florez on his SB 700 [to remove the exemption of agricultural equipment from air quality permitting], I was really excited about that, and I wanted SB 700 to win, to pass. I wanted the governor to sign it. Even though it wasn’t directly related to pesticides, it was air, and air to me is really precious. One time we took a busload of kids to Sacramento, and a lot of the kids had asthma. Instead of taking signs into the Capitol, since you can’t take signs in there, we all wore t-shirts. I still have some. “SB 700 – Our Lungs Count,” or something like that. It was like 150 of us, maybe 100 of us, a busload and some other people in their cars. I sat across from Senator Florez, and this was the summer before the drift accident in Lamont happened. His bill passed, to make a long story short. And he and I were talking, and I was telling him about pesticides and stuff, and he said, “Well you know, this SB 700, it’s not going to touch the pesticides,” and I said, “That’s okay, it’s going in the right direction.” And so he knew me and I knew him. So when this accident happened in Lamont, I called his office. I said, “You need to do something. I mean, this is too much.” And his staffer, Larkin Tackett, said, “Yeah, I’ve gotten other calls.” Larkin goes, “Well let me tell the Senator, and we’ll see what we can do.” And the Senator had a big hearing. He had an investigative hearing right there in Lamont, and that was the best day of my life. I mean, it was just great, because I took people from Earlimart, and Arvin, and then Lamont people. And the Comité Para el Bienestar de Earlimart had a little bit of funding, so we made sure that there was a translator, because Senator Florez wasn’t going to have a translator. And I made sure that there was a babysitter, and that people who lost wages for that day were repaid for what they lost. And so that day was, wow, it was good.

Meanwhile, I had been going to Fresno and meeting a lot of people that were working on air quality. I liked Fresno because there was a cluster of air quality activists. I always liked to work on air stuff, because I know that agriculture had a free ticket. They were exempt from the Clean Air Act. And I thought that was so wrong. So when I learned that Brent Newell was working with Senator Florez on his SB 700 [to remove the exemption of agricultural equipment from air quality permitting], I was really excited about that, and I wanted SB 700 to win, to pass. I wanted the governor to sign it. Even though it wasn’t directly related to pesticides, it was air, and air to me is really precious. One time we took a busload of kids to Sacramento, and a lot of the kids had asthma. Instead of taking signs into the Capitol, since you can’t take signs in there, we all wore t-shirts. I still have some. “SB 700 – Our Lungs Count,” or something like that. It was like 150 of us, maybe 100 of us, a busload and some other people in their cars. I sat across from Senator Florez, and this was the summer before the drift accident in Lamont happened. His bill passed, to make a long story short. And he and I were talking, and I was telling him about pesticides and stuff, and he said, “Well you know, this SB 700, it’s not going to touch the pesticides,” and I said, “That’s okay, it’s going in the right direction.” And so he knew me and I knew him. So when this accident happened in Lamont, I called his office. I said, “You need to do something. I mean, this is too much.” And his staffer, Larkin Tackett, said, “Yeah, I’ve gotten other calls.” Larkin goes, “Well let me tell the Senator, and we’ll see what we can do.” And the Senator had a big hearing. He had an investigative hearing right there in Lamont, and that was the best day of my life. I mean, it was just great, because I took people from Earlimart, and Arvin, and then Lamont people. And the Comité Para el Bienestar de Earlimart had a little bit of funding, so we made sure that there was a translator, because Senator Florez wasn’t going to have a translator. And I made sure that there was a babysitter, and that people who lost wages for that day were repaid for what they lost. And so that day was, wow, it was good.

Before it happened, I told my boss at Californians for Pesticide Reform [where I began working in 2003] that we were going to go talk to Senator Florez. And she goes, “What?” And I go, “Yeah, we’ve got to go over there, because we’re going to talk about the hearing.” And she goes “What, are you kidding?” I said “No, really, he’s going to have a hearing, and he wants us to help.” So we went to his office. Larkin says, “Well, we want to make sure that the questions get to the problem, and we’ll get to the truth. So what are the biggest problems? Or, first, who do we need there?” Well, we want the county ag commissioner there, we want the Office of Environmental Health, Hazard Assessment, OEHHA, we want them there, we want the California Rural Legal Assistance Foundation there. We want Department of Pesticide Regulation. We want Environmental Health there, we want the sheriff, we want the fire department.

I was on the panel with Senator Florez and the [Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment] doctor, Dr. O’Malley. The pesticide in Lamont was called chloropicrin, and it was 100% tear gas, 100%. One of the questions that we told Senator Florez to ask the county ag commissioner was, “Did you give your permission to apply 100% chlorpicrin?” The county ag commissioner said, “No, I didn’t.” And the senator goes, “Well, here’s a paper that says you did. You signed it. Isn’t this your signature?” There were a lot of questions like that where they were just caught with their pants down. It was just so good, all the stuff that came out that day. Another good example – Senator Florez asked Dr. O’Malley, who was on our panel, “When would you consider chloropicrin okay to apply around children?” And Dr. O’Malley said, “Never, I would never consider applying chloropicrin around children because it can damage their lungs. It will damage it.” Senator Florez said, “Well, if they dilute it a little bit…?” and Dr. O’Malley held firm. He said “No, I don’t like it, and I wouldn’t apply it near kids.” So that was great.

Earlimart people told their stories very briefly, because the senator kept saying, “Okay, we’re here to hear about Lamont today. I know these are interesting stories and very important, but we need to hear from Lamont.” And then Arvin people started getting up. Four people from Arvin were just so furious and so angry that they weren’t even told to get out. There was no evacuation for them at all. So the senator was hearing about all these things going on, that nobody even informed them to get out in Arvin. And finally he said, “We need to hear from Lamont, because we only have until such and such time.” So finally, Lamont people started talking. And they said “Well, you know, I live in that housing place, and they never came and took us out. We stood there the whole night. And it was toxic, we were never told it was toxic, nobody went in there to tell us.” Isn’t that weird? After all this stuff and the sick people over here at the store, they never went in and took the rest of the people out. I think if it would’ve been the mayor of Bakersfield or something, they would’ve taken them out. And then that big, husky, macho man that had broken the barricade, he got up there and started talking, and he started crying. And everybody was quiet. It was just so quiet because it was so powerful. He says, “We were told that we couldn’t leave the area, as though we were just worthless. We felt like we just weren’t worth anything. And I saw my kids were sick, and I knew we had to get out, and so I just broke the barricade.” And he started crying. Big man. Oh God, I wanted to go hug him. That was really powerful.

So the senator said, “Well, I’m going to study all this stuff that we got from this hearing, and then we’re going to try to do a couple of things here. We’re going to try to get the medical bills paid for these people. We’re going to try to fix the way the emergency crews handle these emergencies. We’re going to try to have a GPS system so that we’ll know what pesticides are being sprayed where, and that when anything is being called in, that they’ll know it’s a pesticide, and they’ll know which pesticide it is.” That didn’t go through. But anyway, like two months, three months later, SB 391 [the Pesticide Drift Exposure Prevention and Response Act] was written up, and then Senator Florez carried it, and there were lot of trips back and forth to Sacramento with me and a lot of other Earlimart people, Arvin people, Lamont people, back and forth all that year, and then it got signed. By a Republican governor, Schwarzenegger signed it. So it was just a kickass year.

***

Something I’m real proud of is that pesticides and air quality kind of became one. My job at Californians for Pesticide Reform kind of limited me to going to Fresno to air quality meetings. They said, “No, you can’t go because it’s not pesticides.” And I kept saying, “No, no, we are talking about pesticides, because in an indirect way, ozone is caused by pesticides.” And people in Fresno were working on air, mostly air pollution. All of these little bits and pieces kind of magnetized each other and it just all came together. We started having these monthly meetings with Carolina Simunovic, Rey Leon, the Sierra Club, Kevin Hamilton, and then the Women’s League of Women Voters were in it. There were just like seven people. We started meeting and talking about air quality. They knew I was from Earlimart and they knew about pesticides but I would never push my pesticides issue into that stuff. I was very patient. I was trying to just work with them on air quality and help them with that stuff, and then hoping at the same time that they would help with the pesticide stuff whenever we needed it. And sure enough, we formed a real group, CVAQC, the Central Valley Air Quality Coalition. It’s a really important organization now. They have a list of tiers of legislation that they back, and SB 391 [the Pesticide Drift Exposure Prevention and Response Act] was on their top tier. So it’s really good that came to be. And now CVAQ is into solar, into clean energy, the dairies. I don’t want to say it was just me, but little by little, the marriage of pesticides and air quality happened. It had a lot to do with Carolina Simunovic and Rey Leon wanting to learn more about pesticides and going to pesticide conferences. If I hadn’t been going over there and talking to them, I don’t think pesticides would have been in the air quality picture. It’s just good that they were willing to come and do that because in all the towns where they had gone to talk to people, they did pláticas in all these little towns, pesticides was always a top issue for the little towns.

***

I was at a meeting with the county agricultural commissioner, and we were looking at maps of the agricultural land. I saw these little red dots on the map and asked what they were. He said, “Those mark where the bees are, they’re the buffers.” I said, “The bees have buffers and we don’t?!” He said, “Teresa….,” but I was serious.

I was at a meeting with the county agricultural commissioner, and we were looking at maps of the agricultural land. I saw these little red dots on the map and asked what they were. He said, “Those mark where the bees are, they’re the buffers.” I said, “The bees have buffers and we don’t?!” He said, “Teresa….,” but I was serious.

***

I had no idea what an activist was. Now I know there’s a name to it, not just “troublemaker.”

* Pesticide specialists later told the activists from Earlimart that the particular chemical to which they had been exposed is activated by water. They should not have been hosed down as part of the decontamination process.

** The farmer across from Teresa’s home later replanted the edge of the field that she describes as having been taken out of production at the time of this interview.

Interviewer, editor, photographer: Tracy Perkins.

Click on the stars on the left side of this screen for more information.

For more information about Teresa De Anda: